On International Day of Women and Girls in Science, February 11, we are honored to recognize the vital role women play in advancing science. At HDMZ, we see women achieving incredible things at every level across the life sciences, biotech, and healthcare. From the scientific communicators on our team to the founders of game-changing biotechs with whom we partner, women have an immense impact on our work as an agency, and on the world at large.

Raising awareness of the challenges that women and girls face across scientific disciplines is another important piece of observing February 11. To do this, we’ve taken a look at what still needs to change for women in our field, and across science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Here, we bring together some statistics on women’s degrees and careers in STEM, and expert recommendations on how to address the need to better support women’s careers in science.

Representation in postsecondary education

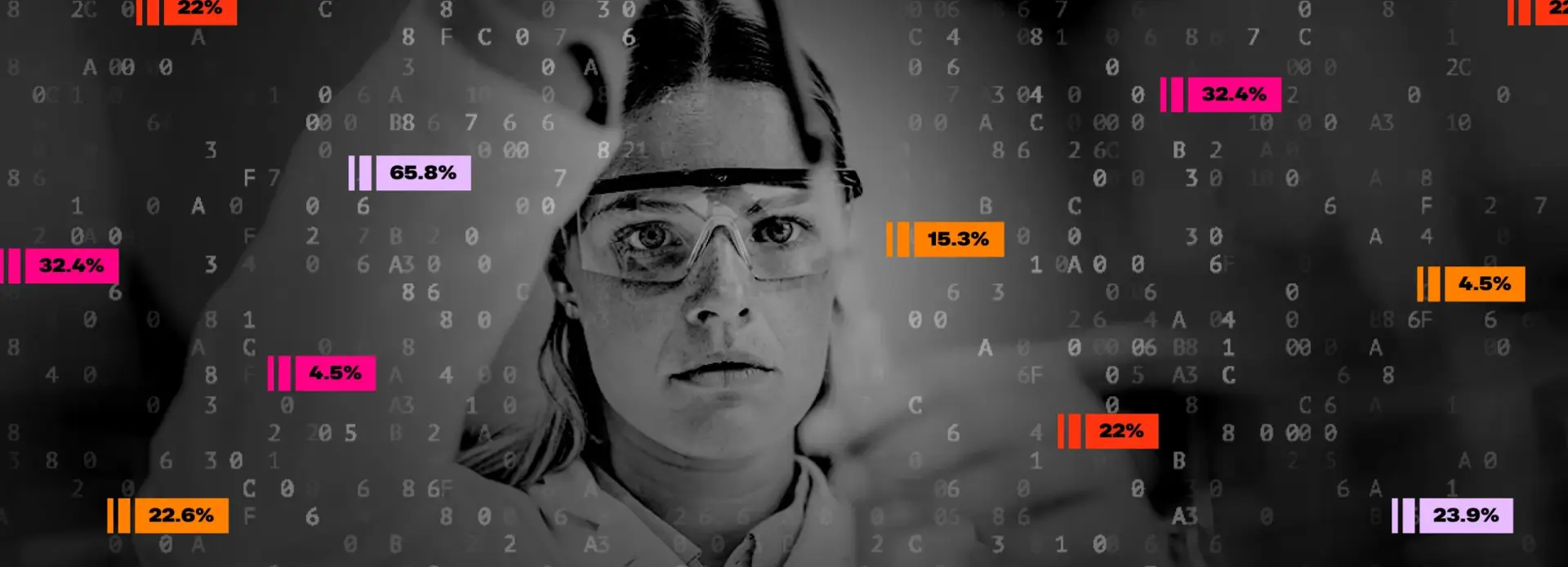

Assessing undergraduate degrees awarded historically paints a picture of how women have progressed over the last 50 years. While in many cases the number of women getting degrees in science has consistently risen, there is still a long way to go. Currently, many scientific areas of study see a disproportionately low percentage of degrees earned by women, compared to the 57.9% of all postsecondary enrollment that was composed of women in 2022.1

Different scientific disciplines have developed in very different ways. There are some scientific fields in which women have flourished. Although women accounted for just 36.1% of biological and biomedical science degrees in 1976, that number has since skyrocketed to 65.8% in 2020.2 In some areas, the proportion of women earning degrees has increased, but there remains a significant gap in representation: For example, engineering saw just 4.5% of degrees go to women in the 1976 academic year, compared to 23% in 2020.3 Other areas, such as computer and information sciences, have remained relatively steady, with 23.9% in 1976 and 22.6% in 2021.4

Gender gaps in the scientific workforce

Frequently, the discussion around women in science centers on fostering girls’ interest in studying STEM subjects. While this is unquestionably an important area of focus, science degrees do not tell the full story. Assessing the gender balance in the work force further contextualizes the challenges women face in STEM careers. For example, in UNESCO member states, women are close to achieving parity in academic and public sector research positions, including in government and private non-profits. However, the private business sector remains male-dominated across all evaluated countries.5

In many cases, women become progressively underrepresented at more advanced career stages. In a 2024 assessment, women held just 22% of STEM jobs in G20 countries.6 Gender representation only becomes more unbalanced when looking at specific fields and positions. For instance, women comprise only 15.3% of the U.S. engineering workforce, even though the percentage of engineering degrees earned by women has been above that number — and rising — since 1995.7,3

These disparities are present even in fields where the matriculation of women has increased hearteningly. Notably, women only made up 32.4% of principal investigators on Clinicaltrials.gov from 2005 to 2023, despite their strong representation in biological and biomedical degrees.8 This means that women are disproportionately missing out on major opportunities for leadership, recognition, and professional advancement. The message is clear: Scientific workplaces need to prioritize supporting women’s careers.

Supporting women’s careers in science

According to UNESCO, many women leave scientific fields due to unsupportive, biased, or even hostile work environments. But, there are many steps employers can take to help support women in scientific careers. Here, we’ve compiled some recommendations from UNESCO and a roundtable on supporting women’s careers in life science and medicine — many of which are practices we utilize ourselves at HDMZ. Good starting places include:

Foster a collaborative, welcoming environment. This goes past just implementing policies and guidelines to address sexism and sexual harassment in the workplace, though, of course, those are crucial first steps. It also means encouraging teamwork among all employees, and building a culture of equality that rewards excellence regardless of gender.

Provide professional development resources. Making leadership and other professional training opportunities available to all employees, or instituting mentorship programs for those entering the workforce, can help provide necessary skills and career guidance for women. Additionally, women-focused employee resource groups can give women critical peer support and networking opportunities.

Support work-life balance. Instituting policies that make it easier for women to navigate societal expectations — for example, caretaking for children or other relatives — can make a huge difference in continuing their scientific careers. Flexible schedules, enhanced parental leave, and remote and part-time options are meaningful policies that can benefit all employees.

Continuing to prioritize women in science

Those who want to go further in advocating for women in science can explore the resources provided by the UNESCO Call to Action to Close the Gender Gap in Science, as well as the recommendations from “Promoting women’s careers in life science and medicine: A position paper from the “International Women in Intensive Medicine” network.”

Additionally, employers can support organizations dedicated to helping women succeed in STEM fields, such as the Association for Women in Science, Women in Bio, and the Society of Women Engineers. They can also connect women on staff with these groups to access networking opportunities, workshops, mentorship, and other resources that meaningfully support career growth.

Although women in science have made progress, they still have a long way to go. Continued improvement in representation and leadership will require a sustained, intentional effort from those with the power to effect change — and from everyone who works alongside women.

References

- Postsecondary National Policy Institute. “Women in Higher Education.” Feb. 2024. https://pnpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/WomeninHigherEd_FactSheet_Feb24.pdf

- Digest of Education Statistics, 2022. Table 325.20. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_325.20.asp?current=yes. Accessed 6 Feb. 2026.

- Digest of Education Statistics, 2022. Table 325.45. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_325.45.asp?current=yes. Accessed 6 Feb. 2026.

- Digest of Education Statistics, 2022. Table 325.35. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_325.35.asp?current=yes. Accessed 6 Feb. 2026.

- UNESCO. “Status and trends of women in science: new insights and sectoral perspectives.” 2025, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000393768

- UNESCO. “UNESCO Launches Imagine a World with More Women in Science’’. 16 Oct. 2025, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-launches-imagine-world-more-women-science-campaign.

- Society of Women Engineers. “Gender Earnings Gap in Engineering Occupations.” All Together, 27 Oct. 2025, https://alltogether.swe.org/2025/10/gender-earnings-gap-in-engineering-occupations/.

- Waldhorn, Ithai, et al. “Gender Gap in Leadership of Clinical Trials.” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 183, no. 12, Dec. 2023, p. 1406. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.5104.